# (launch:thebe)=

# # Defining a finite element ({term}`FE`)

#

# The finite element method is a way of representing a function $u$ in a function space $V$, given $u$

# satisfies a certain partial differential equation.

#

# In this tutorial, we will keep to function spaces $V\subset H^{1}(\Omega)$,

#

# $$

# H^1(\Omega):=\{u\in L^2(\Omega) \text{ and } \nabla u\in L^2(\Omega)\}.

# $$

#

# Next, we need a finite subset of functions in $H^1(\Omega)$, and we call this the finite element space.

# This means that any function in $V$ can be represented as a linear combination of these basis functions

#

# $$u\in V \Leftrightarrow u(x) = \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} u_i \phi_i(x),$$

# where $N$ are the number of basis functions, $\phi_i$ is the $i$-th basis function and $u_i$ are the coefficients.

#

#

# ## Formal definition of a finite element

# A finite element is often described{cite}`ciarlet2002` as a triplet $(R, \mathcal{V}, \mathcal{L})$ where

# - $R\subset \mathbb{R}^n$ is the reference element (often polygon or polyhedron).

# - $\mathcal{\mathcal{V}}$ is a finite-dimensional polynomial space on $R$ with dimension $n$.

# - $\mathcal{L}=\{l_0, \dots, l_{n-1}\}$ is the basis of the dual space

# $\mathcal{V}^*:=\{f:\mathcal{V}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\vert f \text{ is linear}\}.$

#

# One often associates each $l_i$ with a sub-entity of $R$, i.e. a vertex, an edge, a face or the cell itself.

#

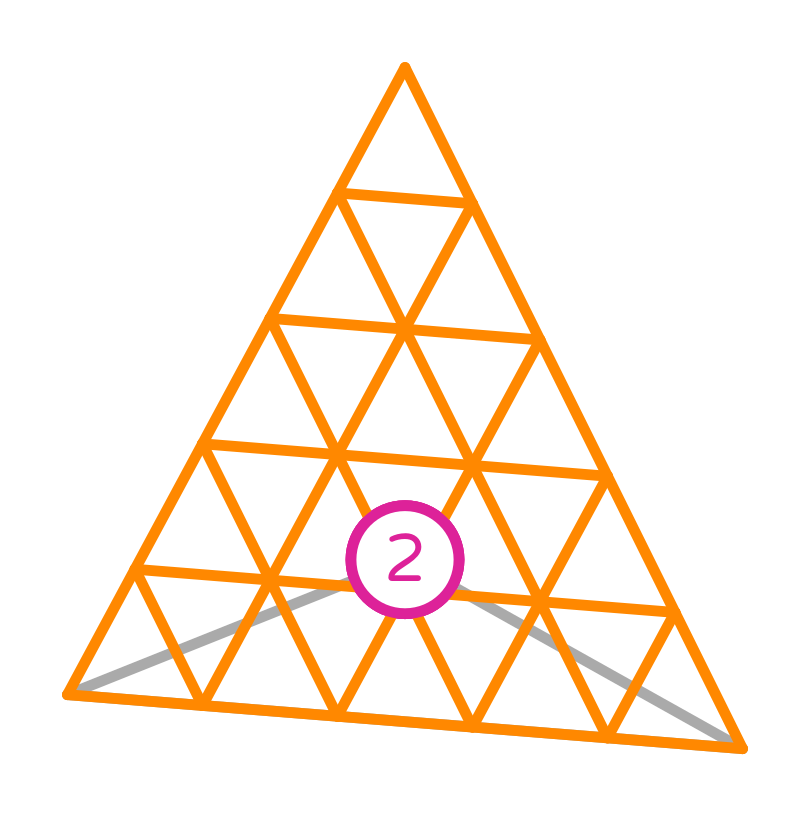

# ## Example: A second order Lagrange space on a quadrilateral

#

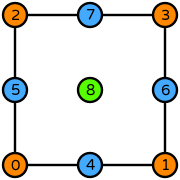

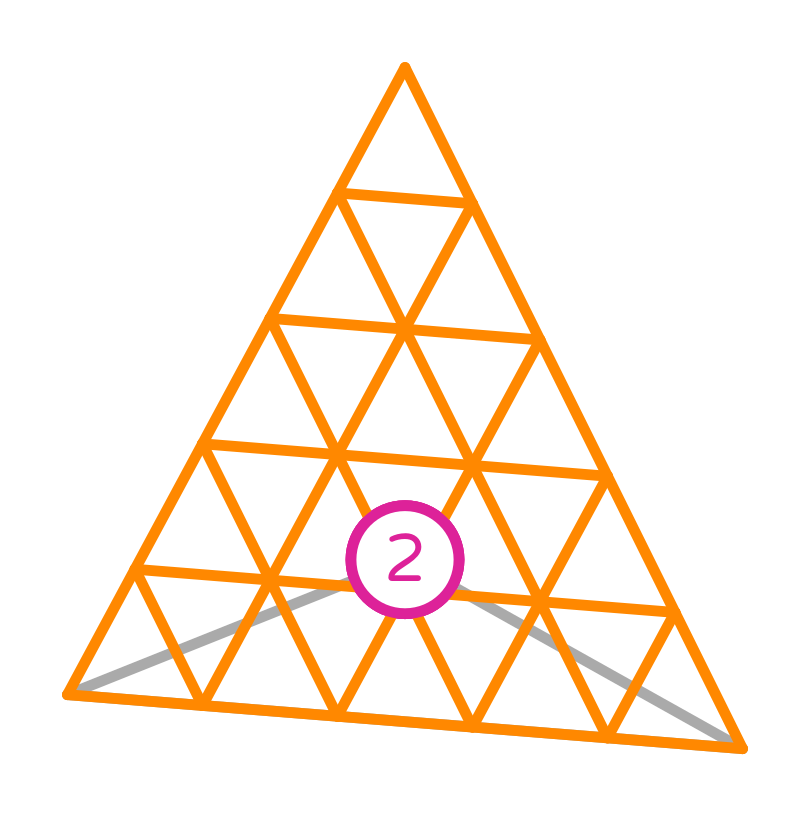

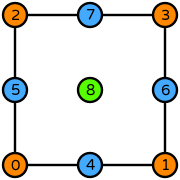

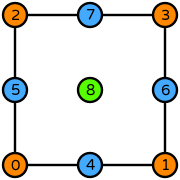

# ```{sidebar}

#

#

# Illustration of dof positioning on a quadrilateral

# (from DefElement, CC BY 4.0).

#

# ```

#

# - $R$ is a quadrilateral with vertices $(0,0)$, $(1,0)$, $(0,1)$ and $(1,1)$.

# - $\mathcal{V}=\mathrm{span}\{1, y, y^2, x, x^2, xy, xy^2, x^2, x^2y, x^2y^2\}$.

# - The basis of the dual space is

#

# $$

# \begin{align*}

# l_0&: v \mapsto v(0,0)\\

# l_1&: v \mapsto v(1,0)\\

# l_2&: v \mapsto v(0,1)\\

# l_3&: v \mapsto v(1,1)\\

# l_4&: v \mapsto v(0.5,0)\\

# l_5&: v \mapsto v(0, 0.5)\\

# l_6&: v \mapsto v(1, 0.5)\\

# l_7&: v \mapsto v(0.5, 1)\\

# l_8&: v \mapsto v(0.5, 0.5)\\

# \end{align*}

# $$

#

# ## Determining the underlying basis functions $\phi_i$

#

# The basis functions are determined by

#

# $$l_i(\phi_j)=\delta_{ij}=\begin{cases}1 \qquad i=j\\ 0 \qquad i \neq j\end{cases}$$

#

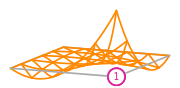

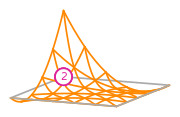

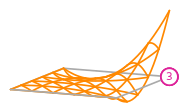

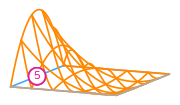

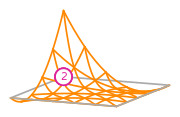

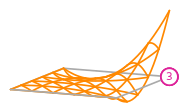

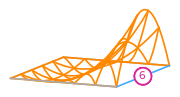

# For the example above this gives us the following basis functions

#

#

#

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#

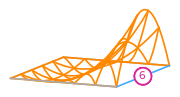

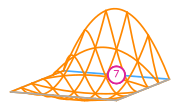

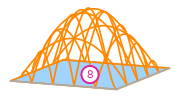

# The basis functions of a second order Lagrange space on a quadrilateral

# (from DefElement, CC BY 4.0).

#

#

#

# ### Uniqueness of basis functions

# This means that we can use different basis functions to span the same polynomial spaces $\mathcal{V}$

# by choosing different dual basis functions $l_i$.

#

# An example of this is choosing different positioning of the dofs (non-equispaced) for Lagrange elements.

# See [FEniCS: Variants of Lagrange Elements](https://docs.fenicsproject.org/dolfinx/v0.9.0/python/demos/demo_lagrange_variants.html)

# for more information.

#

# An algorithmic approach for determining the basis functions based of the dual space is for instance given at

# [Finite elements - analysis and implementation

# (Imperial College London)](https://finite-element.github.io/L2_fespaces.html#vandermonde-matrix-and-unisolvence).

#

# # Creating a finite element in FEniCSx

#

# There is a large variety of finite elements: [List of finite elements](https://defelement.com/elements/index.html).

#

# However, in today's lecture, we will focus on the [Lagrange elements](https://defelement.com/elements/lagrange.html).

#

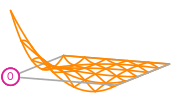

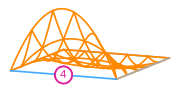

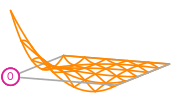

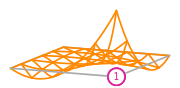

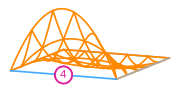

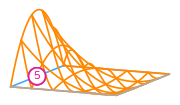

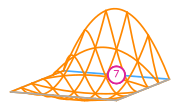

# We start by considering the basis functions of a first order Lagrange element on a triangle:

#

#

#  #

#  #

#

# First order Lagrange basis functions

#

#

# To symbolically represent this element, we use `basix.ufl.element`,

# that creates a representation of a finite element using {term}`Basix`,

# which in turn can be used in the {term}`UFL`.

# +

import numpy as np

import basix.ufl

element = basix.ufl.element("Lagrange", "triangle", 1)

# -

# The three arguments we provide to Basix are the name of the element family, the reference

# cell we would like to use and the degree of the polynomial space.

#

# Next, we will evaluate the basis functions at a certain set of `points` in the reference triangle.

# We call this {term}`tabulation` and we use the `tabulate` method of the element object.

# The two input arguments are:

# 1) The number of spatial derivatives of the basis functions we want to compute.

# 2) A set of input points to evaluate the basis functions at as

# a numpy array of shape `(num_points, reference_cell_dimension)`.

#

# In this case, we want to compute the basis functions themselves, so we set the first argument to 0.

# +

points = np.array([[0.0, 0.1], [0.3, 0.2]])

values = element.tabulate(0, points)

# -

# + tags = ["remove-input"]

print(f"{values=}")

# -

# We can get the first order derivatives of the basis functions by setting the first argument to 1.

# Observe that the output we get from this command also includes the 0th order derivatives.

# Thus we note that the output has the shape `(num_spatial_derivatives+1, num_points, num_basis_functions)`

# +

values = element.tabulate(1, points)

# -

# + tags = ["remove-input"]

print(values)

# -

# ## Visualizing the basis functions

# Next, we create a short script for visualizing the basis functions on the reference element.

# We will for simplicity only consider first order derivatives and triangular or quadrilateral cells.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def plot_basis_functions(element, M: int):

"""Plot the basis functions and the first order derivatives sampled at

`M` points along each direction of an edge of the reference element.

:param element: The basis element

:param M: Number of points

:return: The matplotlib instances for a plot of the basis functions

"""

# We use basix to sample points (uniformly) in the reference cell

points = basix.create_lattice(element.cell_type, M - 1, basix.LatticeType.equispaced, exterior=True)

# We evaluate the basis function and derivatives at the points

values = element.tabulate(1, points)

# Determine the layout of the plots

num_basis_functions = values.shape[2]

num_columns = values.shape[0]

derivative_dir = ["x", "y"]

figs = [

plt.subplots(1, num_columns, layout="tight", subplot_kw={"projection": "3d"})

for i in range(num_basis_functions)

]

colors = plt.rcParams["axes.prop_cycle"]()

for i in range(num_basis_functions):

_, axs = figs[i]

[(ax.set_xlabel("x"), ax.set_ylabel("y")) for ax in axs.flat]

for j in range(num_columns):

ax = axs[j]

ax.scatter(points[:, 0], points[:, 1], values[j, :, i], color=next(colors)["color"])

if j > 0:

ax.set_title(

r"$\partial\phi_{i}/\partial {x_j}$".format(i="{" + f"{i}" + "}", x_j=derivative_dir[j - 1])

)

else:

ax.set_title(r"$\phi_{i}$".format(i="{" + f"{i}" + "}"))

return figs

# ## Basis functions sampled at random points

fig = plot_basis_functions(element, 15)

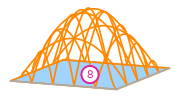

# We also illustrate the procedure on a second order Lagrange element on a quadrilateral, as discussed above.

second_order_element = basix.ufl.element("Lagrange", "quadrilateral", 2, basix.LagrangeVariant.gll_warped)

fig = plot_basis_functions(second_order_element, 12)

# ## Lower precision tabulation

#

# In some cases, one might want to use a lower accuracy for tabulation of basis functions to speed up computations.

# This can be changed in basix by adding `dtype=np.float32` to the element constructor.

low_precision_element = basix.ufl.element("Lagrange", "triangle", 1, dtype=np.float32)

points_low_precision = points.astype(np.float32)

basis_values = low_precision_element.tabulate(0, points_low_precision)

print(f"{basis_values=}\n {basis_values.dtype=}")

# We observe that elements that are close to zero is now an order of magnitude larger than its `np.float64` counterpart.

# ## Exercises

#

# Basix allows for a large variety of extra options to tweak your finite elements, see for instance

# [Variants of Lagrange elements](https://docs.fenicsproject.org/dolfinx/v0.9.0/python/demos/demo_lagrange_variants.html)

# for how to choose the node spacing in a Lagrange element.

# Using the plotting script above, try to plot basis functions of a high order quadrilateral element with different Lagrange variants.

# - Do you observe the same phenomenon on quadrilaterals as on intervals?

# - What about triangles?

#

# ```{admonition} Tip

# :class: dropdown tip

# Try to increase the plotting resolution to 40.

# ```

# ## References

# ```{bibliography}

# :filter: cited and ({"src/finite_element_method/finite_element"} >= docnames)

# ```

#

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#  #

#